Common life offside the Egyptian pyramids

"Fact or fiction?" The pyramids were built by slaves, and the whole ancient Egyptian society was rich and prosperous. Egyptologist Delphine Driaux laughs and clarifies, "Slaves did not build the pyramids. They were free men, who owed service to the king, most probably skilled labourers but also farmers who could not work in the fields during the seasonal floods. The workers were well treated, provided with good food – all being organised by the royal administration."

The heritage of the elite

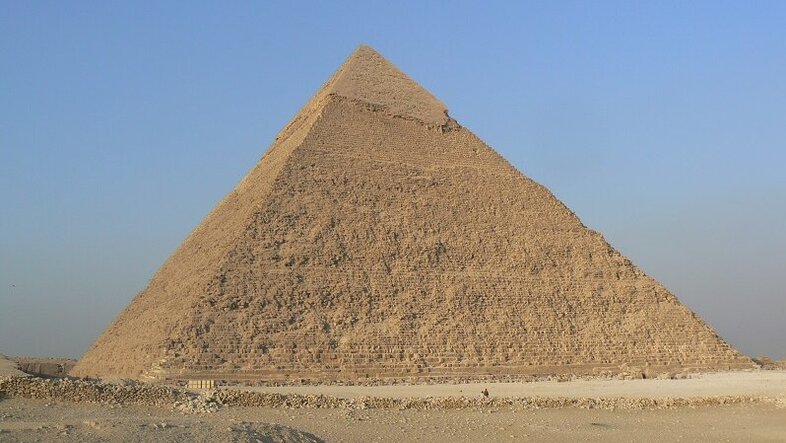

It is no wonder that most people believe that ancient Egypt was a wealthy society as a whole, thinking of the enormous pyramids and the richly decorated tombs full of extraordinary treasures. "But this is only what a small elite left behind. According to estimates, they only were less than ten percent of the whole population, the other 90 percent were normal or poor people," explains Driaux, "Today we just have studied a tiny bit of the Egyptian society while the vast majority has not been studied. In my research, I try to fill this gap and in my studies, I concentrate on the 90 percent of the Egyptian society who is more or less invisible until today."

What we know about the ancient Egyptian society is only one small part of the reality. I hope with the work I am doing I will change the way of thinking a bit.Delphine Driaux

The remains they have (not) left behind

The problem, of course, is that "common people" have not left any writings and are seldomly mentioned in hieroglyphic texts, as Driaux states, "But as more and more scholars start to develop an interest in Ancient Egypt's majority society, we also begin to find more evidence." Very promising is a cemetery found during the archaeological mission by Anna Stevens from the University of Cambridge, in which Delphine Driaux also participated, "We found it at the famous site of Armana, a capital city under Pharaoh Akhenaten. It is very likely a non-elitarian cemetery because there are just very small tombs cut in sand and the people were buried only wrapped in linen and a mat. So here you can consider that you are dealing with less privileged people."

In order to gain more knowledge about the living conditions of these people, Driaux works together with so called osteologists, experts in the "reading" of bones. The skeletons of Armana tell the scientists a story of a hard life, "The ones we found are in bad condition, showing a lot of abrasions, which means that they had poor health and worked very hard."

If you just look at what is nice and shiny, and you ignore the entire other part of society, you build what G. Levi called 'a mystified society'.Delphine Driaux

Graves for the less privileged

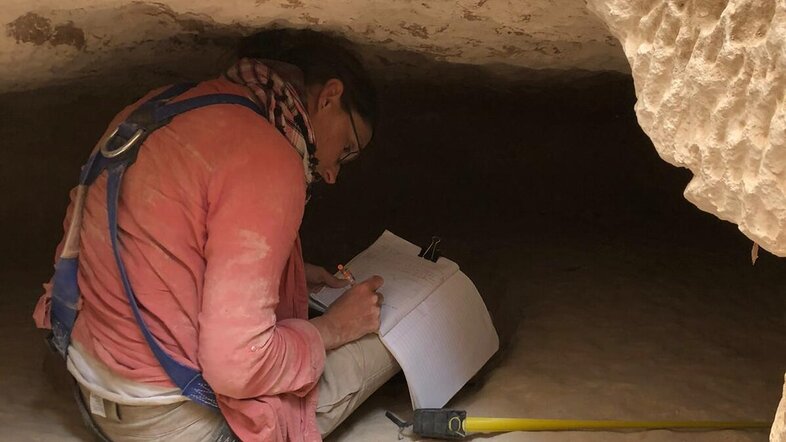

One task in her project is to go through the documentation, the topography of former or existing excavation sites to see if the "poor" tombs have merely been neglected by the archaeologists. Driaux hopes to find less privileged graves on the excavations she is in charge of, in particular, at el-Sheikh Fadl in the framework of the University of Vienna Middle Egypt Project. So far, she and her team have found mainly large tombs, but Driaux is confident that she might come across some hidden graves, "Next year, I want to develop a new survey of the area to see if there are places that could contain ‘poor’ tombs. It would be great if we can find them because it would mean that my idea is valid, that there are spaces that seem inhospitable but were actually used for the less privileged."

Reading documents in a new way

Apart from searching for archaeological finds from the non-elite of Ancient Egypt, Delphine Driaux is also taking a new approach to existing written and iconographic sources, "The idea is to go back. Many texts are very famous and very well studied but no one really cared so far about the small descriptions of normal people we can find there." Her aim is to analyse the texts and images anew, gather archaeological data and combine all this information.

It is more than work, it is a passion.Delphine Driaux

"Normal people look all the same"

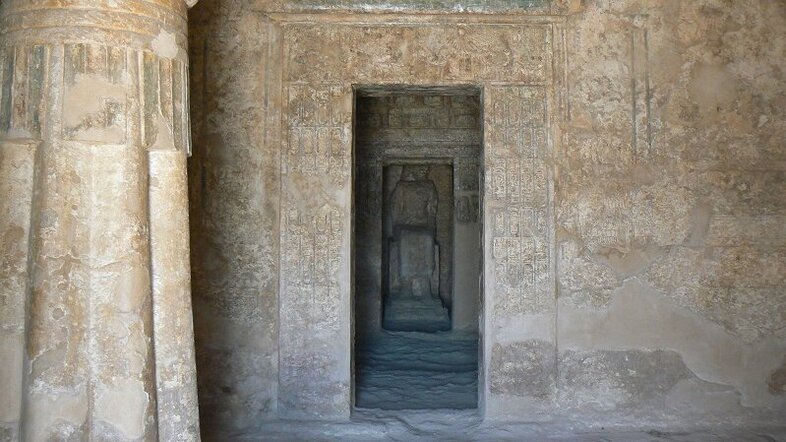

Interesting insights into "normal life" can, for example, be found in the decorations of some tombs of wealthy people, "A common motif is a picture of the owner of the tomb looking at his farmers working for him or his servants bringing offerings," says the archaeologist, "The owner is easy to identify as he is always depicted very tall. Persons of inferior status are smaller, look all alike, have characteristic tools and have no name or title inscribed. In addition to ensuring the continuity of the deceased's life in the afterlife, they show also the power and wealth of the deceased."

Looking at the main aims of her challenging project Driaux concludes, "All the documents, paintings and written texts have been produced by the elite for the elite, so it is very subjective and we have to be critical about that. I hope that combining the information of these three different sources – texts, images and archaeological artefacts –will give us a better understanding of what the lives of the non-elite and also of poverty looked like."

She is currently Deputy Director of the University of Vienna Middle Egypt Project and is in charge of the excavations of the necropolis of el-Sheikh Fadl. In 2021, Delphine Driaux was awarded the Elise Richter grant by the FWF with which she realises the project Representations and Reality of Poverty in Ancient Egypt.