Migration and new beginnings: The history of displaced persons in Austria

"Compared to the Second World War and the post-war period, even the major waves of migration of 2015 and 2017 only account for a fraction of this," says contemporary historian Kerstin von Lingen, who is currently leading two major projects on migration and the post-war period. "You can no longer research national history today, and we do not want to. We are interested in the transnational connections of migration flows after the Second World War." As part of the FWF project “Norms, Regulation and Refugee Agency”, the contemporary historians are investigating the migration flows that started from Austrian displaced persons (DP) camps, while the ERC project explores the interactions between the involvement of the Allies and humanitarian organisations in DP camps in Europe and Asia.

In 1945, Austria was a poor country which had suffered massive destruction in the war. At the end of the war, refugees accounted for around five per cent of the total population and most of them were accommodated in large displaced person camps. "One of the largest camps in Austria was located in Linz. It accommodated 10,000 people who were waiting for a better life, most of whom wanted to emigrate overseas. We call this state ‘being in transit' and it could sometimes take two or three years," says project leader Kerstin von Lingen.

International conference: Being in Transit from 25 to 27 May 2025

The conference ‘Being in Transit’ will take place as part of the ERC project ‘GLORE. Global Resettlement Regimes: Ambivalent Lessons learned from the Postwar (1945-1951)’ from 25 to 27 May 2025 at the Hotel Regina. The contributions presented at the conference offer insights into very different and yet often simultaneous forms of ‘Being in Transit’. They analyse the spaces, networks and continuities of transit, ranging from specific places to international paths along which people and ideas can travel, and discuss places of refuge in Europe, Asia, North and South America, Africa and Oceania.

More information about the international conference

Download the full programme (PDF)

Marriage programme Down Under

"In the course of our research, we naturally come across incredibly exciting and often moving stories," says von Lingen, "It is particularly interesting when we examine such movements for entire population groups." Australia is a good example here, as the country gained independence from Great Britain only in 1931 and pursued a very active population policy after the end of the war. The research team found documents in which Australia ‘ordered’ displaced persons, e.g. they needed "another 10,000 workers" for new factories, preferably from Poland or the Baltic states, "blond migrants are preferred". "That is no joke, it is really phrased like that in the documents. There were also separate marriage programmes for women to be married to Australian farmers, for example," says the contemporary historian.

Book tip on the topic: Displaced Knowledge

The book “Refugees from National Socialism in Australia. A History of Displaced Knowledge” by Philipp Strobl traces the ideas and knowledge that migrated in the cultural baggage of Austrian refugees who fled to Australia because of National Socialism. Twenty-six very different stories tell of the transfer of cultural capital, such as of a man from Tyrol who successfully built the first ski lifts in the Australian Blue Mountains.

Stages of a life

On both the ERC Advanced Grant GLORE project "Global Resettlement Regimes: Ambivalent Lessons learned from the Postwar (1945-1951)" and the FWF project "Norms, Regulation and Refugee Agency: Negotiating the Migration Regimes", Kerstin von Lingen and her team collaborate closely with the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies at the University of Osnabrück. There, they work with Christoph Rass and his team who analyse historical migration data, such as accommodation, ship and aircraft passenger lists, etc., which are stored in the Arolsen Archives for archiving and further research purposes.

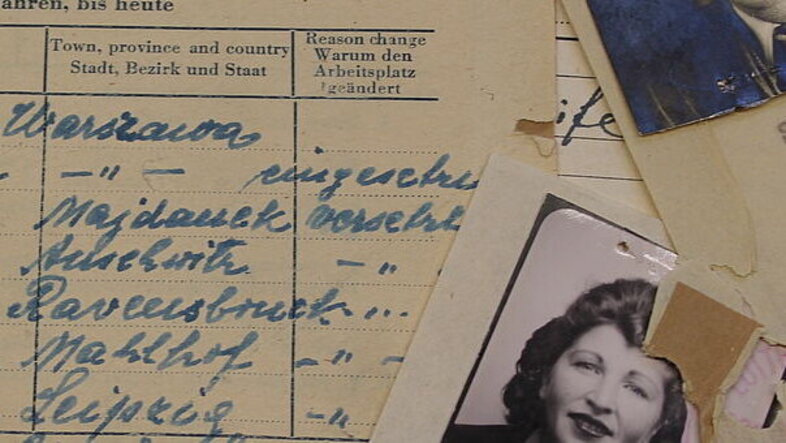

In addition, the Allies issued a ‘personal file card’ for each displaced person, which specified the stations of their migration and ideally ended with their final destination, such as Canada. "There are over 14 million data sets in total, so it is impossible to process all of it in a researcher's lifetime," says von Lingen, "The Allies used these personal file cards to obtain an overview of the post-war camps: Who survived? Where do the people come from, where do they want to go? And that is also the idea behind our projects: We want to make these movements visible and identify patterns.”

Visualising life paths using digital humanities

The researchers have access to the Arolsen Archives, an extensive database which allows them to filter accordingly. "We define and focus on sample groups, such as children under the age of five in the Allied camps in Austria. On this basis, we then continue to explore whether these children were there with their parents or just their mother, etc.," explains von Lingen.

On a larger scale, for example, the lives of 10,000 displaced persons from Austrian camps can be visualised. The contemporary historians discovered that there was a major migration flow to Paraguay in November 1946. The files show that the authorities in Paraguay had reported a need for labourers at the time and 30,000 people were therefore resettled in one fell swoop.

80 years after the end of the war – events at the Faculty of Historical and Cultural Studies

On 8 May 2025, we celebrate the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. This day marks the unconditional surrender of the German Wehrmacht and the end of one of the most devastating wars in human history. Eighty years after the end of the war, keeping the memory alive remains a central task. Dealing with the lessons of this period is crucial for preserving peace and democracy. To the events (web page in German)

No mothers wanted

Such large data sets enable researchers to address fascinating questions in detail. For example, Franziska M. Lamp-Miechowiecki is investigating single-mother families in Austrian camps as part of her doctoral thesis conducted in the framework of the FWF project “Norms, Regulation and Refugee Agency”. Here, the focus is on women who were forced to migrate without a male head of the household. "Many families were torn apart back then, with the men often missing or dead. This was often difficult for these women because the host countries were not at all interested in a single mother of four children, for example," says von Lingen. "Many therefore pursued a clear strategy. Since it was generally quicker to travel abroad as a family, they married in the camp and travelled to Australia or the US as a family. After arriving there, the spouses parted ways."

The dilemma of the ethnic Germans

In another project, contemporary historian Philipp Strobl is researching ethnic German (‘Volksdeutsche’) groups and how Austria dealt with them. "As an academic, it is very important to me to also research the forced migration of Volksdeutsche and to get it out of the 'right-wing corner'," emphasises von Lingen: "If we consider the ethnic Germans as a migration group after 1945, who were also dependent on the aid of the Allies, then of course we see very similar logistical problems as in the case of the former forced labourers or the survivors of the Holocaust. How are they accommodated? Where do they find work? How to continue?"

In 1945, the Danube Swabians were suddenly told that they were Germans and would be resettled to Germany, but neither the Allies nor Austria felt responsible for them. Many were stuck in camps for years without access to food supplies or the labour market. "Some of these are stories of massive social exclusion. Especially in the Catholic rural areas of Austria, Volksdeutsche were outsiders, also because many of them were Protestants."

Transit. The podcast on migration history

Franziska Lamp-Miechowiecki and Philipp Strobl talk to experts about key topics in 20th century migration history as part of the "Transit" podcast initiated by the Department of Contemporary History. In the podcast series, expert knowledge on migration history is presented in the form of clear interviews. The podcast is available on popular podcast platforms such as Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music and Podbean, as well as on the project website. To the podcast

Tragic return

Of course, there are also tragic fates among Holocaust survivors who finally returned to Poland after being liberated from Mauthausen or Dachau and found that they were left with nothing: their villages were empty, their relatives were dead, and in the cities, their neighbours had often taken over their homes. "These are very brutal stories. Many of the survivors then made their way back to Germany or Austria with the last of their strength to wait in the camps until they were taken overseas by the Allies to a better future," says von Lingen.

The Allies and the International Refugee Organization (IRO) ensured that the long journeys to emigration were paid for. "After all, it is always about money. If I have just survived a concentration camp, I cannot afford a boat ticket for the crossing over to Australia. These journeys were often sponsored by companies, such as the pharmaceutical society in the case of Australia, which paid for 10,000 workers to travel to the country."

The organisation of migration movements

Many different bodies were responsible for the orderly organisation of repatriation and emigration after the end of the war, from the UN and the Allies to national authorities, churches and interest groups such as the Jewish Community in Austria. "As an administration you do not want everyone to set off individually and end up stranded somewhere," says von Lingen. "Migrants have to be managed, everything should be organised and regulated." The trips were organised in the camps and people were managed using the above-mentioned personal file cards. "Many of the displaced persons had nothing to lose and did not want to go home or even stay in Europe. This gives the whole issue a global dimension, also because Australia and Canada in particular were opening up to labour migration. That is how these long, long journeys come about – and they are exciting to research."

Project details: Migration flows in the post-war period

“Norms, Regulation and Refugee Agency: Negotiating the Migration Regimes”, (Displacement and Resettlement in Austria after 1945), 2022-2025, FWF project (DACH funding scheme, in collaboration with the University of Osnabrück, Christoph Rass and Frank Wolff).

This project argues that the migration and refugee movements after the Second World War led to the establishment of new migration regimes. The project presents a new, actor-based history of the handling of migration movements in Austria and Germany after the end of the Second World War.

“Global Resettlement Regimes: Ambivalent Lessons learned from the Postwar (1945-1951)”, (Displaced Persons in Europe and Asia after 1945 in a global perspective), 2023-2028, ERC Advanced Grant GLORE.

This project presents the idea that global resettlement regimes have developed in the late 1940s and in the 1950s. Previous research on displacement and resettlement has generally considered the post-war experiences in Europe (after the Holocaust) and in Asia (e.g. in China) separate from each other. In contrast, this project outlines the connections between the European and Asian spheres and links them with Australia and America.

- Focus: Learning from the past

- Department of Contemporary History

- Website of Kerstin von Lingen

- „Norms, Regulation and Refugee Agency: Negotiating the Migration Regimes“

- ERC Advanced Grant GLORE “Global Resettlement Regimes: Ambivalent Lessons learned from the Postwar (1945-1951)”

- Transit. The podcast on migration history