How inclusive is our healthcare system really?

Nobody likes to see the dentist – but when plagued by a toothache, we are all grateful to receive quick and easy help. However, for around 89,000 people with intellectual disabilities in Austria, reality is different. Health psychologist Elisabeth Zeilinger explains: "People from this group always have somebody else, a relative or caregiver, who is responsible for their care. This caregiver needs to first notice that the person is in pain, because people with disabilities may not be able to directly communicate discomfort. Instead, their reaction to pain often manifests as challenging behaviour, which the caregiver must interpret correctly." Zeilinger is head of the Intellectual Disabilities research group at the Department of Clinical and Health Psychology at the University of Vienna.

Who are we talking about?

Their research focuses on people who have experienced impairments during their developmental years, i.e., before the age of 18. These impairments can result from chromosomal or genetic causes, such as trisomy 21 (Down's syndrome), exposure to harmful substances during pregnancy, or complications during childbirth, such as a lack of oxygen. In most cases, however, the causes are unknown. "An IQ score below 70 as well as deficits in adaptive behaviours that affect everyday living, such as shopping, washing yourself, reading and writing, are typical signs of an intellectual disability," explains Zeilinger. For better inclusion of this group, it is important to consider the reality of their lives ‒ for example by scrutinizing the language we use to communicate with them.

Zeilinger and her team are conducting, among other research strategies, qualitative interviews with affected individuals and their caregivers. The results have shown that providing appropriate healthcare to these individuals requires a great deal of perseverance, time and communication with committed doctors. In addition, there are many practical obstacles, such as mobility, accessibility and challenging situations.

"For example, long waiting times paired with a wide range of stimuli in an unknown environment can be overwhelming. Many people have reported feeling eyeballed in the waiting room," says Theresa Wagner, doctoral candidate in Zeilinger’s team. The researchers agree that the healthcare system does not adequately take this group into account – despite the fact that Austria has ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2008, which guarantees equal opportunities in healthcare.

More cancer deaths due to insufficient prevention

Lack of inclusion has fatal consequences. "International studies have shown that in people with intellectual disabilities, cancer is often detected at a late stage, resulting in higher mortality rates," says Zeilinger. One key research area of her team is cancer screening programmes, in particular for breast and colorectal cancer. "The mammography carried out as part of breast cancer screening is usually conducted on patients in an upright position. This is a problem for female individuals who need to use a wheelchair. Furthermore, documents are often hard to understand and are not translated into easy-to-read language, which results in communication barriers," says Wagner.

World Cancer Day on 4 February

The World Cancer Day serves to demonstrate the importance of prevention, cancer screening and research on cancer. It aims to raise awareness of the disease and promote measures aimed at improving care and treatment.

There are steps in the right direction: A national colorectal cancer screening programme is currently being planned, which should provide new impetus in the field of inclusion. Zeilinger and her team have conducted interviews with 31 people with intellectual disabilities and 13 caregivers to identify specific barriers and supportive factors, which they compiled in a results report. The findings from this and other projects will be considered in the new version of the national cancer programme by the Federal Ministry of Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection. Elisabeth Zeilinger and Theresa Wagner were invited to join the expert group focusing on equal opportunities. "The great thing is that this allows us to integrate aspects relating to inclusion in the development of this programme from the start," says Zeilinger.

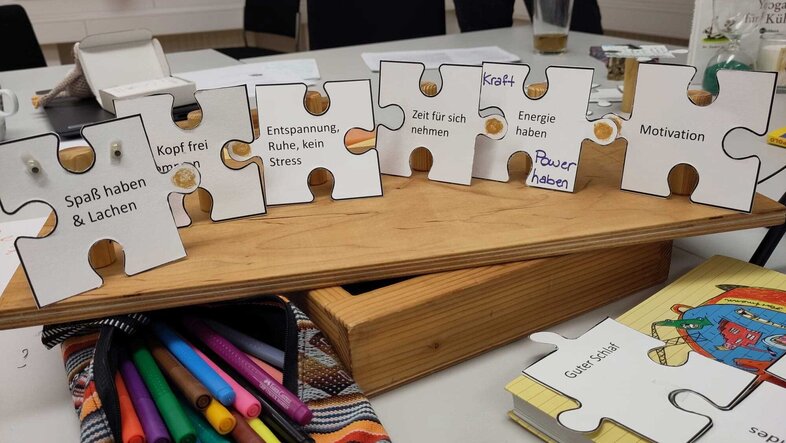

To actively include people with intellectual disabilities in research, the health psychologist and her team have to come up with creative solutions. Having worked as care staff in a supported housing facility for people with disabilities, Zeilinger has valuable personal experience in that field. For example, she and her team developed jigsaw puzzles to make abstract topics such as mental health tangible and to jointly develop definitions. Common models often deny this group of persons the ability to ever enjoy mental health. "As long as I do not understand how this group defines mental health, I cannot take effective measures that are supposed to benefit them," the researcher emphasises. In general, the health situation of people with intellectual disabilities is not sufficiently measured.

According to Zeilinger, the lack of data is partly a result of the crimes committed against this group of people during the Nazi era. In order to protect this group, there are still justified reservations concerning the collection of their data. As a result, Austrian health statistics, which provide the basis for the planning of healthcare structures, do not contain any data on people with intellectual disabilities. The consequence: There are no specific provisions for this group in the Austrian healthcare system.

By creating anonymised registers, which exists in other countries, we could significantly contribute to improving our healthcare system. "I consider it our responsibility to provide the lacking data as a sort of service to the system. This is essential for political change, since evidence-based findings cannot easily be ignored," Zeilinger points out. "Austria has an obligation towards these people, especially in light of its history, and has to support and improve their situation in life through research." The Intellectual Disabilities working group is currently only funded by third-party funds acquired by Zeilinger.

Just like her own research, healthcare for people with intellectual disabilities has relied too heavily on specific individuals, regrets Zeilinger. "Medicine, psychology and other disciplines hardly address this issue during education and training. The only way that students – often coincidentally – hear about this topic is usually when committed teachers offer elective courses on it," explains Zeilinger. It would be better if universities can commit to including relevant content in their curricula to raise awareness and allow students to acquire the necessary competences.

"Intellectual disabilities are invisible because they generally have a weak presence in society," says Zeilinger. But inclusion should not be a marginal issue – neither in kindergarten, nor on the labour market or when you have a toothache. Especially in the healthcare sector, we have to make sure that nobody is excluded.

Focus of the research group

The Intellectual Disabilities research group addresses mental, social and health aspects relating to intellectual disabilities. Their aim is to improve the quality of life of affected people in various areas and stages of life as well as to promote equal opportunities with regard to health and healthcare. Their approach is based on models of positive psychology and theories of self-determination, and has a clear focus on the human rights perspective. Further information about the research group.

- Research group "Intellectual Disabilities"

- Project results report: Colorectal cancer screenings for people with intellectual disabilities

- Systematic overview of literature on the health situation of people with intellectual disabilities, Federal Ministry of Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection (in German)

- Associations and disability organisations (in German)