Cancer research

Survival of the fittest cells

29. March 2022

by

Hanna Möller

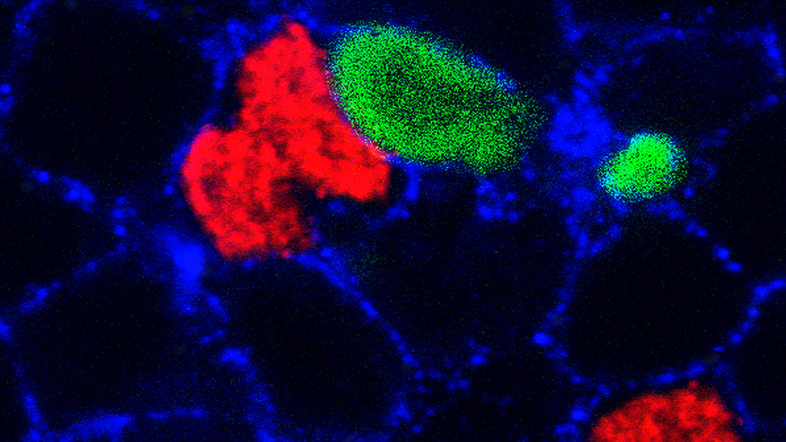

Stephanie Ellis is uncovering the principles of cell competition at the Max Perutz Labs. By understanding how our system eliminates 'loser' cells, she gains knowledge for future cancer therapies.

Read now