Women’s pain: An ignored reality in medicine

A current estimate states that approximately 1.8 million people in Austria are suffering from chronic pain. According to recent numbers from the Austrian pain society, the majority of these patients are female, explains neuroscientist Manuela Schmidt. Working with a team of 11 researchers at the University of Vienna, she is investigating the molecular mechanisms of chronic pain to optimise future treatment strategies.

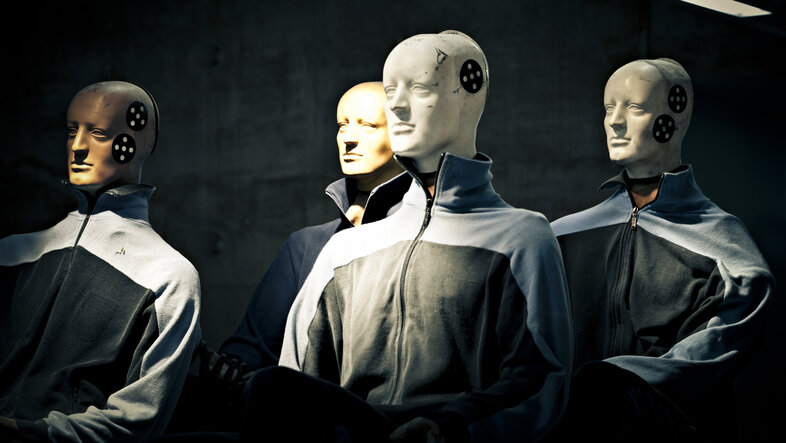

Most painkillers on the market are quite old. What is ‘new’ are merely their variations, says Schmidt. When the precursors of our painkillers were approved, studies involving only male participants were the standard. "Until approximately ten years ago, preclinical care still focused on middle-aged Caucasian men," which is surprising since most patients suffering from chronic pain are female. Why is this the case? What are the consequences of this disparity?

Focus on the male norm

On the one hand, "practical and ethical reasons" were decisive, Manuela Schmidt reports, who supervises several preclinical studies running at the same time: It is easier to experiment with homogeneous groups and the results are easier to compare. Since there is always a risk that the active substances in the drugs may affect female reproductive capacities, the default choice was the male sex. On the other hand, as in many other areas as well, the focus on the male norm means that "medication has been developed without taking reality into account for a long time," adds medical ethicist Magdalena Eitenberger. She works on gender medicine at the Department of Political Science at the University of Vienna.

The field of pain research has developed significantly in the last few years: "In order for preclinical research to reflect our diverse society, serious studies need to at least compare gender," says Manuela Schmidt. Together with her team, she was able to show that the protein Tmem160 delays pain development in nerve injury, but only in male individuals (see publication). "This is a prime example of why it is important to analyse the sexes individually. If we had looked at both sexes together, we would have seen a medium, non-significant effect."

When we analyse inequality in research and medicine, we quickly come to the conclusion that the Caucasian, healthy, male body is the standard and everything else is considered a deviation.Magdalena Eitenberger

However, we still have a long way to go to address diversity in research, adds Eitenberger. We still do not consider obese people, both male and female, menopausal women, people of colour or transgender persons in preclinical studies. "We do not need technologies made for the ‘norm’. What we need are designs for studies, medication and structures in the health care system that aim towards a broad and diverse population," Eitenberger emphasises.

Barriers and racism in the health care system

Some diseases are more prevalent in certain population groups, such as sickle cell anaemia in Equatorial Africa. This is a hereditary disease in which the red blood cells take on the shape of a sickle limiting the transport of oxygen, with severe consequences for the patients. Patients suffer from reduced blood circulation in their organs leading to organ damage, an increased risk of stroke or infection and, in some cases, severe pain, explains Manuela Schmidt. Yet carriers of this genetic trait show a relative resistance against malaria. This is quite beneficial in malaria regions and the reason why the trait is commonly observed in individuals of Equatorial African descent.

"We still do not know enough about this," argues Eitenberger who takes an intersectional approach in her research. People of colour are less represented in research and there should be broader approaches for diverse population groups, agrees Schmidt. Furthermore, "statistics clearly show that, due to historical racism, people of colour are treated differently during medical examinations, e.g. they are prescribed painkillers less frequently for the same symptoms," adds Eitenberger.

Same symptoms, different attributions

Other diseases are more common than others among the female sex. Fibromyalgia is a chronic pain disorder that especially affects the joints and leads to serious discomfort. It is a disease that, from a genetic point of view, affects women more frequently than men, says Schmidt. Persistent migraine and back pain, which are the most common reason for being unable to work, are not specifically female diseases, but women report them earlier and more often. In this case, Schmidt and Eitenberger assume psychosocial causes, which still reflect a 'traditional' gender image: "Women are more likely to admit that they are in pain, while there seems to be a higher psychological barrier among men."

However, this 'traditional' image of gender also means that the symptoms experienced by female patients are more likely to be attributed to psychological causes: "Their experiences are often not sufficiently taken into consideration and their physical symptoms are quickly dismissed as ‘this is all in the mind’," explains medical ethicist Eitenberger. This means that formal diagnoses are often delayed for longer periods of time while the symptoms remain unrecognized.

FEMtech – is technology the solution?

A rather positive development, according to Eitenberger, is that nowadays, the female menstrual cycle is receiving more attention in medical research. "Many medications have a different effect depending on the menstrual cycle. The strength and severity of chronic illnesses also vary according to the cycle." Medical technology has also been expanded to include a new category: FEMtech. It comprises technology-based applications designed to meet the needs of women, including period trackers, smart tampons, pregnancy assistants on the smartphone or contraception apps. But not every person perceived as a woman has a menstrual cycle, Eitenberger adds, criticising the narrow image of women that many FEMtech features support: "It propagates the idea of a woman who regulates and optimises herself and is the one responsible for their own contraception and reproduction. Menstruation should be one category, among many others, integrated in medical apps for everyone.

Talking about ‘for everyone’: Eitenberger repeatedly emphasises that focusing on two sexes is dangerous in the debate on gender medicine. "When we look for differences, we will find them". But gender is a very fluid category and depends on many factors. "Our medical approaches must be as diverse as our society." (hm)

After career stages in Würzburg, Germany, California and Göttingen, she came to the University of Vienna in 2020. She is Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Life Sciences.

Before joining the Department of Political Science in 2023, Magdalena Eitenberger worked at the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Digital Health and Patient Safety and at the Department for Ethics and Law in Medicine and as a project manager at the Federal Ministry of Social Affairs, Health and Consumer Protection during the COVID-19 pandemic.