When thawing permafrost releases greenhouse gas

The hum of an engine and a shrill screeches in the Canadian tundra: four people in rubber boots and weatherproof jackets lean with all their body weight on a drill rod. Piece by piece, the thread drills its way into the frozen ground. Extracting samples from permafrost is backbreaking work. After a few minutes, the researchers pull out the drill and extract a core of frozen soil and ice - eight centimetres in diameter, almost half a metre long: permafrost. This permafrost reaches more than 100 metres deep into the Earth's interior and never thaws. Technically. "The Arctic has been warming for decades and now at a speed four times faster than the rest of the world,” says Andreas Richter, head of the Centre for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science at the University of Vienna, ecologist and polar researcher. "When permafrost thaws, it doesn't just change the Arctic landscape. This thawing can also increase global warming,” he explains.

Arctic Science Summit Week 2023

From 17 to 24 February 2023, 700 scientists from all over the world are meeting for the annual Arctic Science Summit Week (ASSW); this year's venue is the main building of the University of Vienna. The discussion agenda includes the clearly noticeable effects of climate change on the Arctic and the consequences for the rest of the world.

The networking meeting is organised by the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC), hosted by the Austrian Polar Research Institute (APRI), which also includes numerous scientists from the University of Vienna.

This year's ASSW Science Symposium (21-24 February) is dedicated to the topic "The Arctic in the Anthropocene" – researchers, students and representatives from politics and economy are invited to discuss the burning issues of polar research.

Greenhouse gases that enhance climate warming

The reason for this lies in the processes that are triggered by thawing. Trapped in the permafrost are dead plant remains and humus, and thus, also organic carbon and nitrogen. Permafrost soils hold one of the world's largest pools of organic carbon and global nitrogen. When the soils and soil-ice mixtures thaw, microbes become active and break down these compounds. As a result, they produce greenhouse gases that enhance climate warming: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), but also nitrous oxide (N2O). Nitrous oxide is a greenhouse gas with about 300 times the warming potential of CO2. Microbes produce it from nitrogen released during the decomposition of organic material. However, it is not yet known exactly how these processes take place in thawing permafrost.

The Arctic has been warming for decades and now at a speed four times faster than the rest of the world.Andreas Richter

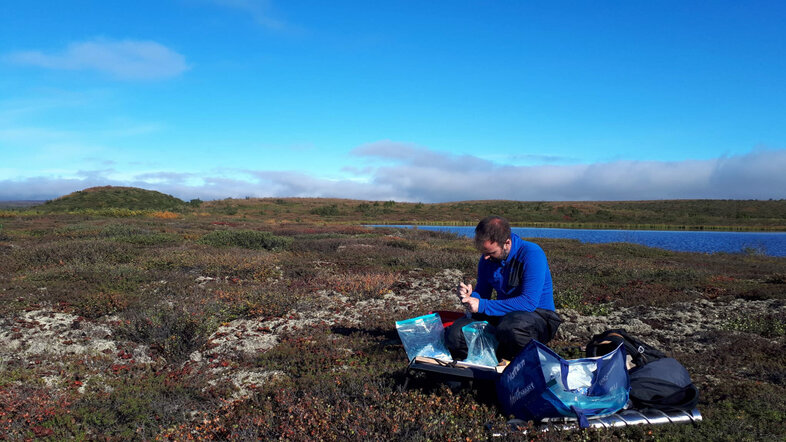

"It's incredible how little we know about it, considering that nitrous oxide has a stronger warming potential than CO2,” says Nicolas Valiente Parra, a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science. That's why he just spent three weeks on the road. Together with Andreas Richter and other researchers from Austria, Belgium and Sweden, they collected soil samples in an area along the Dempster Highway, a dust road connecting Inuvik, a small town in northwestern Canada, and Tuktoyaktuk, the second northernmost community on the Canadian mainland.

Vast landscapes that change and reshape

Valiente Parra is researching the nitrogen cycle in the so-called thermokarst landscape in Canada's far north. Thermokarst occurs when lenses or wedges of ice, often several metres in diameter, thaw in permafrost soils. While frozen ground thaws slowly, ice thaws much faster. Such abrupt thawing processes may cause the ground to collapse, eroding coastal areas and creating vast landscapes of small lakes that change and reshape with each freeze and thaw period. "I was really impressed when I first saw with my own eyes how far this landscape stretches," says the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) Programme fellow. "And I was surprised how exhausting it is to collect soil samples here”, he laughs. The biogeochemist just shifted his focus from water bodies to soils with this project.

Many Inuvik residents tell us about their relatives who live in the coastal area. They struggle with the fact that the soil around their houses is eroding and the drinking water supply is regularly at risk.Victoria Sophie Martin

The research team spent twelve hours a day in the field. "Here in the Arctic summer there is light for a long time,” Andreas Richter says. About six to nine drillings a day were doable. Each sample site had to be prepared for about an hour: The researchers recorded the soil structure, noted the plants growing here and dug through the first half metre of the soil, the so-called active layer, with the shovel. This active layer thaws again and again with the seasons. Beneath it, the permanently frozen ground begins. Satellite images show that it continues to thaw in the coastal area of the Canadian Arctic. "We can see that many of the lakes here have been getting bigger for at least 30 years,” explains Andreas Richter. "However, we cannot conclusively say to what extent there are other causes besides global warming that are causing the landscape to change rapidly here,” he adds.

The ground melting away

What the researchers outside of their field research trips are able to see on satellite images only is tangible for the local inhabitants in their everyday lives. "Some people there are literally watching the ground melt away from under their feet,” says Victoria Sophie Martin. She is doing her PhD on the temperature adaptation of polar microorganisms and has already been here in 2018 and 2019 together with Andreas Richter. "Many Inuvik residents tell us about their relatives who live in the coastal area. They struggle with the fact that the soil around their houses is eroding and the drinking water supply is regularly at risk,” she reports.

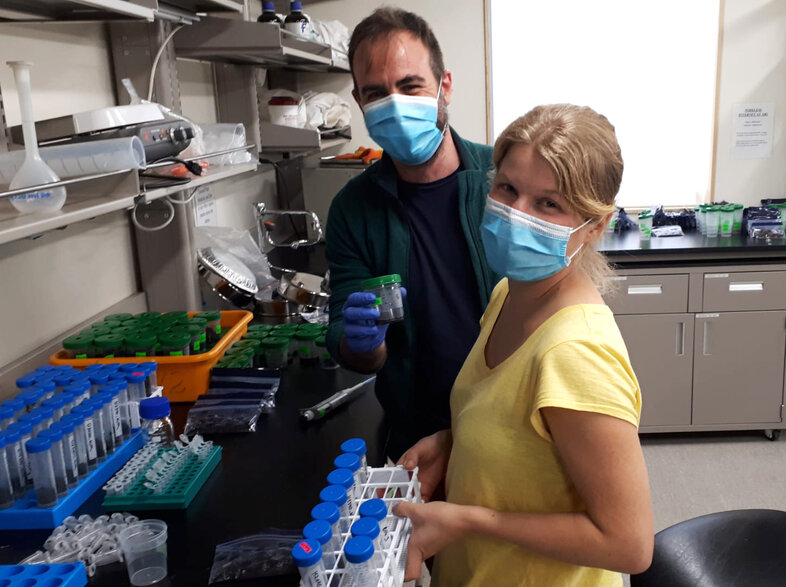

In order to get a realistic picture of which processes the microbes trigger in the thawing Arctic soil and how these processes not only boost climate change, but also affect the concrete living situation of the local people in the long term, the researchers had to conduct experiments directly on site and prepare the soil samples for further analyses. "We thawed some of the soil samples over several days to simulate a natural thawing process. Then we added proteins with labelled nitrogen to them and incubated them in airtight containers,” Nicolas Valiente Parra explains. "After a few days, we then sampled the greenhouse gases produced and obtained extracts from the soil samples to determine which compounds the organic material had been converted to and which microorganisms were responsible for it.” These samples were brought back to Vienna and will be analysed in the laboratories of the Centre for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science. "We will use different analyses to determine what the microbes did with the nitrogen and then we will also know, among other things, how much nitrous oxide they have produced", Valiente Parra says.

Several dozen kilograms of samples

The researchers collected about 50 drill cores with frozen Arctic soil, as well as a large number of plant, water, and soil samples in the Arctic. To Vienna they brought back not only the gas samples and soil extracts obtained from them. The Viennese ecosystem researchers had several dozen kilograms of samples in their luggage. A good half of it is frozen soil: large pieces of frozen earth, each weighing about seven kilograms. "In cooperation with the GFZ Helmholtz Centre Potsdam, we will simulate freeze and thaw cycles in these soil samples over several months in a special incubator set up by our colleagues in Potsdam," explains Nicolas Valiente. "In this way, we want to simulate and trace how the processing of nitrogen in Arctic soils takes place over the course of the seasons.” The researchers hope that this will enable them to further investigate the possible feedback effects between the thawing of permafrost soils and climate warming.

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101024321.