The University of Vienna in the period of Austrofascism

As a historian at the Department of Contemporary History of the University of Vienna I have explored the past of ‘my’ alma mater in the period between 1933 and 1938 for many years. With my book ‘Die Universität Wien im Austrofaschismus’ (the University of Vienna in the period of Austrofascism), I have entered uncharted academic territory since it is the first monograph published on this topic – completely contrary to the numerous studies on the role of the University during National Socialism. My research brought to light new aspects of Austrofascism. I demonstrated how the Dollfuss/Schuschnigg regime operated, how it instrumentalised the University for political purposes and how this caused considerable damage to the University of Vienna.

Book recommendation

While there are countless studies on Austria’s universities after the “Anschluss” in 1938, the five years before have hardly been covered in terms of university history. Linda Erker's book closes this research gap, which impressively shows how much the University of Vienna suffered under the Dollfuß/Schuschnigg dictatorship.

Linda Erker was recently awarded the Michael-Mitterauer recognition prize for this book. In 2022, she also won the Irma Rosenberg Prize for research on the history of National Socialism awarded by the Austrian Society for Contemporary History.

Linda Erker: Die Universität Wien im Austrofaschismus [in German]. V&R unipress, Göttingen 2021.

Austria’s first dictatorship

For the period between 1933 and 1938, we can differentiate three stages of the political instrumentalisation of the University of Vienna: The first stage began with the parliament being dissolved in March 1933 and lasted until the proclamation of the constitution in May and the Nazi Putsch in July 1934. In this period, an authoritarian structure was imposed on the students’ representation for which the federal ministry appointed representatives – so-called ‘Sachwalter’ (agents) of the new ‘Hochschülerschaft Österreichs’ (national union of students of Austria), which is the predecessor of the Austrian National Union of Students (ÖH).

In addition, measures against National Socialist as well as leftist students were tightened. The regime intervened in an authoritarian way in everyday university operations already in the autumn of 1933. For example, the regime introduced university guards in charge of surveilling the academic terrain. Also the number of disciplinary procedures on account of prohibited political activity increased threefold from 1933 to 1934 – pursuing the aim of exerting political control over the academic realm by all available means.

Furthermore, the patriotic education of young people became a task of the Alma Mater Rudolphina in addition to research and teaching whose academic freedom was restricted. In 1935, compulsory ideological lectures and university camps were introduced, aiming at providing pre-military training and religious education to male students in the summer months. This authoritarian and totalitarian approach to education was inspired by Fascism.

In particular, the University’s teaching staff was affected by heavy interventions from 1933/1934 onwards due to cost-cutting measures as well as due to measures aimed at political ‘cleansing’. In total, around 25 per cent of all professors were dismissed – one of the deepest cuts in the long history of the University. A disproportionately high share of professors suggested for (early) retirement by the University were of Jewish descent. The National Socialist teachers who had to leave the University moved to the German Reich to pursue their careers. In 1941, the National Socialists at the University of Vienna awarded them the title of ‘Honorary Senator’.

However, my research also shows that the University of Vienna was already a stronghold of National Socialists and anti-Semites before 1938 and even long before 1933. Psychological and physical violence as well as racially motivated anti-Semitism had characterised everyday life of students already since the 1920s. The National Socialist movement had dominated among students already from the early 1930s onwards – supported by many anti-Semitic professors who shaped the University and systematically thwarted the careers of Jewish and leftist scholars after World War I. Academics identifying with Christian Social, German National and later National Socialist ideologies cooperated very successfully already then.

Anti-Semitic continuities

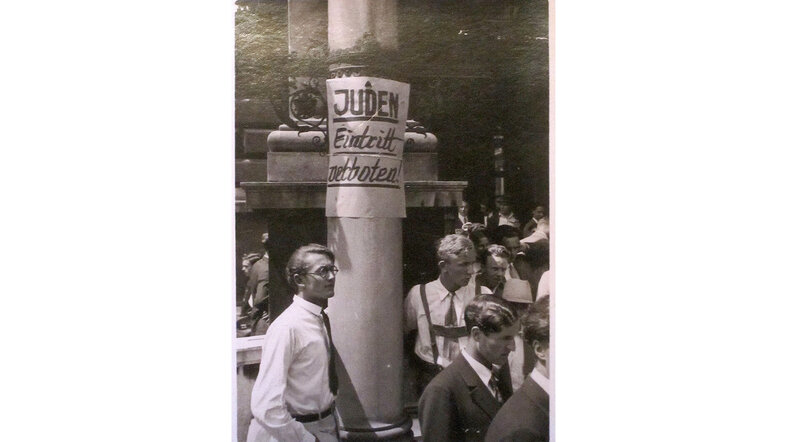

Anti-Semitic sentiments at the University of Vienna long before 1938 are a core topic in my monograph, which contains a wide range of examples for this. Already in 1931, a poster stating ‘Jews keep out’ was put up on a signpost in front of the University. This was seven years before the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by the German Reich, in 1938.

Dating to the same year, 1931, we have a photo of a parade of National Socialist students carrying torches and giving the Nazi salute in front of the main entrance of the University – with former Rector Hans Uebersberger right in the centre. In the autumn of 1931, the Nazis carried out brutal attacks, beating up Jewish students at the University. On 9 May 1933, students were forced to flee a lecture through the window because Nazis carrying wooden clubs and brass knuckles had positioned themselves in front of the lecture hall.

We know from the biography of a Jewish student (Benno Weiser Varon) that he had equipped himself with a large key and key ring as a weapon on his first day at University to be able to defend himself if necessary. Pen and paper seemed less important to him. In the case of the murder of Moritz Schlick, professor of Philosophy at the University, by the mentally ill Hans Nelböck in June 1936, the retrospective reports on the event also demonstrate the enormous dimension of anti-Semitism at the University of Vienna. Schlick was not Jewish himself but was considered pro-Jewish.

Jewish students and professors had been gradually expelled or kept away from the University of Vienna already since the 1920s which, of course, bled the intellectual potential dry. Many of them took the necessary steps: Young Jewish and leftist teachers pursued careers outside university, mainly at adult education centres. These brilliant minds never returned to the University. Several, including Marie Jahoda, Max Perutz, Otto Neurath, Julius Tandler or Karl Menger, left the country – some voluntarily, some were forced to leave.

Press conference: Problematic honours at the University of Vienna

Since 1865, the University of Vienna has honoured personalities who are of special significance in the context of the University's history. Some of these are historical figures who have made anti-Semitic, racist or fascist statements or actions. The University of Vienna is now reviewing its honours practice. In a University-wide project, 1,577 honours awarded so far have been examined. The aim is to identify, contextualise and make visible so-called problematic honours. This was achieved by adding relevant information to the biographies on the 650plus website and by marking them accordingly. The project was presented on 24 October 2023 (see press release in German).

‘Autochthonous provincialisation’ and the return of the old elite

The dictatorship also left traces in the long term. My study shows the developments at the University following the Anschluss in 1938 as well as after the end of World War II. to identify the ruptures and continuities of Austrofascism.

For example, after the Anschluss, the National Socialists used an Austrofascist law to revoke teachers’ entitlement to teach for racist and political reasons. With the establishment of the Second Republic in 1945, especially human resources policy at the University continued as in the years before 1938. Sociologist Christian Fleck from Graz coined an accurate term in this context. He talks about the ‘autochthonous provincialisation’ after the War. He argued that successive dismissals, the reinstatement of former Austrofascists, and the failure to invite scientists who had emigrated for political or racial reasons resulted in a low intellectual quality among scholars in post-war Austria.

The Main Building of the University of Vienna on Ringstrasse had been heavily damaged by bombings. And yet: 1945 was not the ‘zero hour’ – this is a myth. Immediately after the end of the war, former officials of the Dollfuss/Schuschnigg regime returned to educational policy and to their key academic positions at the University, the Academy of Sciences and the Federal Ministry.

Ludwig Adamovich senior, the last minister of justice during Austrofascism, became the first Rector of the University after World War II. Heinrich Drimmel, who had been appointed in 1934 by the Federal Government as senior students' representative at the University of Vienna and later even as students' representative for all of Austria, first became head of department in the Federal Ministry of Education before being appointed as Federal Minister in 1954. In that capacity, he also brought back Nazis to the universities. Josef Klaus, Drimmel’s predecessor as students’ representative, was Federal Chancellor from 1964 to 1970 (both for the Austrian People’s Party, ÖVP). Both got along very well with anti-Semitic, German National and National Socialist colleagues before 1933/1934.

Another continuity: The Cartellverband (Union of Catholic German Student Fraternities) was a central recruitment pool for top positions, especially during the Dollfuss/Schuschnigg regime – and then again after 1945, in particular, but not only at universities. Therefore, we can truly say that the University of Vienna experienced an ‘extended interwar period’ with a Catholic-authoritarian note which lasted until the 1960s.

To put my study in a nutshell, you could say: Various stakeholders instrumentalised the University of Vienna between 1933 and 1938: The first Austrian dictatorship as well as teachers and students acting in their own interests as the discrimination against and expulsion of colleagues and fellow students shows. The government introduced saving measures which the University used to carry out both political and anti-Semitic ‘cleansing’ of its teaching staff. At the same time, the authorities interfered with university and student self-administration by means of new laws. This provincialisation began in 1933/1934 and seamlessly continued after 1945 when university executive positions were consistently staffed with former Austrofascist officials.

In addition to her academic work, she has been engaged for many years in the non-academic dissemination of historical knowledge with a focus on public history and on the history and consequences of National Socialism in Austria.