The climate debate – Between lobbies and science

Rudolphina: Stefan Rahmstorf, you are one of the most renowned climatologists and a leading oceanographer and palaeoclimatologist. You first studied physics and then physical oceanography. When did your enthusiasm for your research topic begin?

Stefan Rahmstorf: Very early, actually: I grew up in Holland, and the North Sea awakened my enthusiasm for the sea. Later, when I was studying physics, I realised that it was also possible to use physics to conduct marine research. In fact, it was one book in particular that fascinated and interested me, "The Drama of the Oceans", written in 1975 by the maritime lawyer and ecologist Elisabeth Mann Borgese. When I read it, I thought, “Wow, that is actually a great research topic”, and then I started studying physical oceanography at the University of Wales in Bangor.

Environment and Climate Research Hub (ECH)

The Environment and Climate Research Hub (ECH) is a new multidisciplinary research network within the University of Vienna. It is dedicated to connecting researchers addressing environment, climate, and sustainability from different academic viewpoints. More about the objectives of the network.

Currently, the ECH has 65 members from different faculties and departments of the University of Vienna. All of them carry out research in the field of environment and climate. Thilo Hofmann is co-heading the ECH together with Sabine Pahl.

Read the report of the launch and watch the video of the keynote and panel discussion.

Rudolphina: As a palaeoclimate researcher, you study the climatic conditions of the Earth's past in order to make predictions about the future development of the climate on our planet. What can we learn from the ice age?

Stefan Rahmstorf: The most important lesson we can learn from this for our future is the so-called climate sensitivity, the reaction to known perturbations in the Earth's radiation balance. Climate sensitivity tells us the extent to which the global temperature responds to changes, for example, how much warming is caused by a doubling of CO2. The answer is about three degrees. The fact that the climate has always reacted strongly to disturbances in the radiation balance in the past is a lesson from the ice age. And then there are other lessons, such as about the instability of ocean circulation. This is the background to the concern that the circulation of the Atlantic could break off, because this has happened several times in the Earth's history, for example when temperatures on Earth warmed after the last ice age.

Rudolphina: You raise an issue that's been much discussed recently: The possible collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which is of great importance for the relatively mild temperatures in Europe. As an oceanographer, you have been researching this topic for some time: Can this collapse still be stopped? If not, when would we feel the effects around the world?

Stefan Rahmstorf: When we talk about the consequences, we are talking about what will happen when we have passed the tipping point. But we do not yet know when and if global warming will reach that point. What is clear, however, is that from that point onwards, the dynamics would run their course within a few decades. However, we could minimise this risk if we consistently abide by the Paris Agreement and keep global warming well below two degrees.

Rudolphina: And what happens if we pass the so-called tipping point and AMOC stops?

Stefan Rahmstorf:

Stefan Rahmstorf: If the AMOC were to collapse, the effects would indeed be fatal: there would be strong regional cooling, not only over the ocean, but also over land areas in north-western Europe. According to a new study by the Utrecht University, which has just been published in the media, the Norwegian coast could be 20 to 30 degrees colder in winter.

But that is by no means the only consequence. The tropical rain belts would shift southwards. These rain belts would then no longer fit over the rainforests, where they actually belong. As a consequence, some forests would dry out or burn down, while there would be heavy rainfall in regions where people are not adapted to it.

Another problem is that the ocean's uptake of oxygen and CO2 would be greatly reduced if the AMOC were to collapse. This is because it is driven by water that sinks to depths of 3,000 metres. If this stops, the deep ocean will be deprived of oxygen. This would disrupt the marine ecosystem, with consequences we cannot yet foresee.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

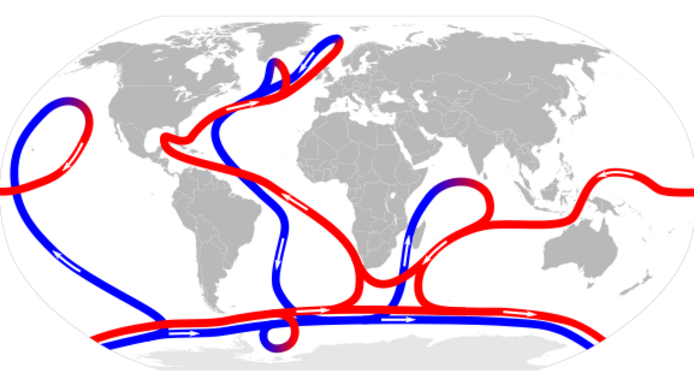

The Gulf Stream, AMOC and the "global conveyer belt"

In the 2004 disaster film "The Day After Tomorrow", the Gulf Stream collapses, triggering an ice age. Contrary to popular belief, however, the Gulf Stream cannot collapse. When it comes to ocean currents, mix-ups and confusion are commonplace. Here is an overview of the three most important terms:

The Gulf Stream owes its name to the Gulf of Mexico, where the water masses supplied from the equator press against the North American coast. From there, it flows northwards and north-eastwards, with part of it passing by the British Isles and northern Europe.

The Gulf Stream is driven by global wind systems and the Earth's rotation. As long as the Earth continues to rotate, the current will not come to a halt.

The Gulf Stream feeds part of the largest current system in the ocean, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). In the upper layers, warm, salty water flows from the South Atlantic to the North Atlantic. There it cools down and drops like a gigantic waterfall to a depth of 2-3 kilometres. The deep waters then return to the south. During this process, energy in the form of heat is released into the air, which influences the climate in northern Europe. The circulation pump is driven by differences in temperature and salt concentration in the ocean. When warm surface water (red in the figure above) evaporates, its salt concentration increases and thus its density. Dense water (blue) sinks to the bottom and cools down at depth. AMOC is part of the so-called "thermohaline circulation" (from the Greek thermós "warm" and halos = "salt"), which spans the world's oceans like a "global conveyor belt" in a cycle.

If the Greenland ice melts due to climate change, a lot of fresh water will enter the AMOC. This could prevent the water in the North Atlantic from sinking, which could bring AMOC to a standstill. Simulations on the latest climate models confirm this possibility.

Rudolphina: In your keynote speech you say that all reputable scientists agree that modern global warming is around 100 per cent caused by humans. However, many people still believe that this is much more controversial among scientists. Why is that?

Stefan Rahmstorf: One reason is the lobbying of fossil fuel companies and some multi-billionaires who fund the so-called climate sceptics, their appearances and publications. Rupert Murdoch, for example, uses his media empire to promote statements by climate sceptics that are intended to raise doubt. But I also see a problem with other media that try to be balanced: they keep putting sceptics on talk shows, even though they have no scientific expertise, and then pretend that they are broadcasting a scientific debate. For the public, this is confusing and misleading.

It is our duty as scientists to educate and warn the public.Stefan Rahmstorf

Rudolphina: In your opinion, is it also up to scientists to make their voices heard in politics?

Stefan Rahmstorf: It is definitely the job of scientists to warn of dangers. After all, I also expect a doctor to tell me, "If you continue to smoke, your risk of lung cancer will increase". And we scientists have to communicate in the same way: We have evidence that if we continue to emit CO2, it will get warmer, which will lead to rising sea levels and extreme weather events with all their consequences. As scientists, we are paid by the public and should act in the public interest. It is therefore our duty to educate and warn the public.

Rudolphina: You are publicly presenting your research findings. Why is this exchange so important for you?

Stefan Rahmstorf: On the one hand, even as a schoolboy and student I benefited a lot from popular science in books or magazines. At that time, the enthusiasm for science simply gripped me. And I want to pass on this enthusiasm for science and research. But of course, I also want to inform people about the dangers and warn them about the consequences.

Rudolphina: To move on to our current semester question on AI and knowledge: What potential do you see with regard to the use of AI in climate research?

Stefan Rahmstorf: Of course, climate research uses such methods. For example, studies have shown how AI can be trained using very good, high-resolution climate models, which are however very expensive in terms of computing time. We can make climate models faster and cheaper, for example, by using a coarser model of this AI to generate higher-resolution precipitation patterns.

Rudolphina: Will AI make predictions more accurate?

Stefan Rahmstorf: Yes, that is the hope, of course. Climate models generate huge amounts of data, and using AI to sift through the data and identify patterns is a hot, relatively new topic at the moment. As scientists, we are also interested in the physical mechanisms behind the patterns we identify. We must not accept them as a black box, because AI can also make mistakes. We should thus not rely on it blindly.

Rudolphina: What is the impact of AI on our climate? In terms of resource consumption, what footprint do data and AI leave? And what are the consequences?

Stefan Rahmstorf: I do not know any specific figures, but it has to be said that even conventional computer simulations, which we run on high-performance computers, use a lot of electricity. This makes it all the more important to increasingly run such calculations on renewable electricity. We are on the right track here in Germany – at least we are moving in the right direction. Nevertheless, it is of course also important in research to pay attention to minimising the use of data and to efficiency when it comes to energy consumption.

His research focuses on palaeoclimate, changes in ocean circulation and the sea level as well as extreme weather events. Rahmstorf often addresses the topic of global warming in public lectures as a keynote speaker or in the RealClimate blog, which he co-founded. He also wrote several popular books about the state of the climate and oceans.

Read the long version of this interview on the website of the Research Network Environment and Climate.