Nobel Prize in Economics: Do we need democracy for prosperity?

They distinguish between "inclusive" institutions, which facilitate productive activity, as opposed to "extractive" ones, which favour rent-seeking behaviour. Rent-seeking refers to the act of increasing one's wealth without contributing to society's overall wealth, such as by bribing policymakers to prevent competitors from entering the market.

Some examples of inclusive institutions are:

- Widespread property rights, which permit actors to keep the returns from their investments, and thus encourage productive activity;

- Equal opportunities, which enable those with good ideas (rather than those with wealth) to implement their projects, and thereby enhance productivity;

- Democracy, a disciplining device useful to ensure that governments provide the public goods needed for economies to thrive.

Democracy makes it more likely that governments support basic science, maintain the rule of law and justice, regulate malfunctioning markets - and ensure that the rules of the game are in the interest of society at large.

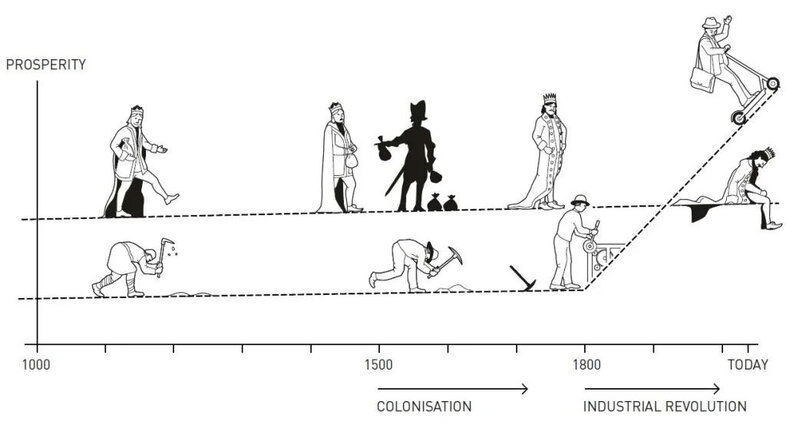

Concentration of wealth and power limits economic prosperity

Institutions tend to evolve as the result of the interaction between economic and political power: in the presence of large wealth disparities within a nation, for example, rich elites may capture the state and impose institutions favouring their political dominance and economic interests over those of the people. Unfettered political power allows authoritarian leaders to change economic rules to their own benefit and that of their supporters, limiting economic opportunities for the majority of society. With checks and balances in place, however, the political system can promote the establishment of property rights and equal opportunities for all.

The concentration of wealth and political power in the hands of a wealthy elite or authoritarian leaders can create an institutional status quo that hinders prosperity. In contrast, more egalitarian distributions of wealth and political power tend to foster a prosperity-inducing status quo. However, the status quo is sometimes disrupted by changes in technology or historical ‘accidents’. For example, the flourishing of trans-Atlantic trade led to the appearance of a new group: merchants. Together with other groups, they were powerful enough to prevent absolutism from establishing itself in England. More recently, the technological advancements of the last fifty years has led to a large concentration of economic power in a few hands that may endanger democracy.

Learning from the colonial past

Establishing these causal links between a society's institutions and economic prosperity was not an easy task. A correlation between the two does not mean that one is the cause of the other. In their empirical work, Acemoglu and colleagues made clever use of colonial history to solve this problem.

Their findings are sobering. In colonies where the environment made it difficult for European settlers to stay due to high disease risk, such as West Africa, they imposed extractive institutions aimed at the exploitation of native populations and resources. This perpetuated high degrees of inequality and poor economic performance. In benign environments, such as North America, Europeans settled instead in larger numbers and gave themselves inclusive institutions; this led in turn to larger prosperity. Similarly, colonies with high population densities ‒ a sign of development ‒ were more likely to be subjected to extractive institutions than sparsely populated ones; this gave rise to a "reversal of fortune" whereby the latter are nowadays richer than the former.

New Institutional Economics teaches us that the slow but persistent dismantling of the system of checks and balances ‒ on which liberal democracy is based ‒ is a serious concern. In general, we cannot take the survival of democracy for granted, as the present situation in the US ‒ with a substantial influence of wealth on politics ‒ suggests. China's performance of the last four decades may be seen as a challenge to this research agenda, since the high concentration of political power has not hindered the country's spectacular growth. However, there may be a lesson for the future here. After all, Acemoglu, Robinson and Johnson also teach us that the effects of institutions become apparent only in the long run.

His work focuses on Development Economics, International Economics and Macroeconomics. He often looks into the implications of international economic relations on macroeconomic outcomes (income per capita, economic growth, business cycles), but also does research on the determinants of trade patterns and the behavior of firms in the open economy.

- Website of Alejandro Cuñat

- Department of Economics

- Reading recommendation: Why Nations Fail by Daron Acemoğlu and James Robinson

- Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson: Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth

- The Prize in Economic Sciences 2024: Short essay by the Nobel Prize Outreach