The social network of our cells

The cells are the smallest components of life – and the ones that keep our system going by making many smart decisions in every millisecond. Communication is key: Our cells interpret the signals from the environment and translate them into the right output. If something goes wrong in signalling, serious diseases, including cancer, may develop. Manuela Baccarini, Professor of Cell Signalling at the Max Perutz Labs, has been interested in this process since the start of her career in molecular biology. In Rudolphina, she talks about the ’signaling highway’ in our bodies and about the way high throughput technologies revolutionised modern molecular cell biology research.

Rudolphina: Manuela Baccarini, what is the big question you are trying to answer?

Manuela Baccarini: I would like to understand the ways our cells communicate with each other. On the one hand, they communicate long distance through soluble mediators that play an important role, for instance, in the regulation of immune reactions. On the other hand, they ’talk’ to each other through direct contact. I am particularly interested in the ERK signal transduction cascade, which has been dubbed ’signaling highway’. Most signals – no matter how they are transmitted – use this pathway to carry the signals from the cell surface through the cell and into the nucleus. The results of this range from cell shape or metabolism change – and constitutive activation may lead to up to cell transformation.

A dangerous highway

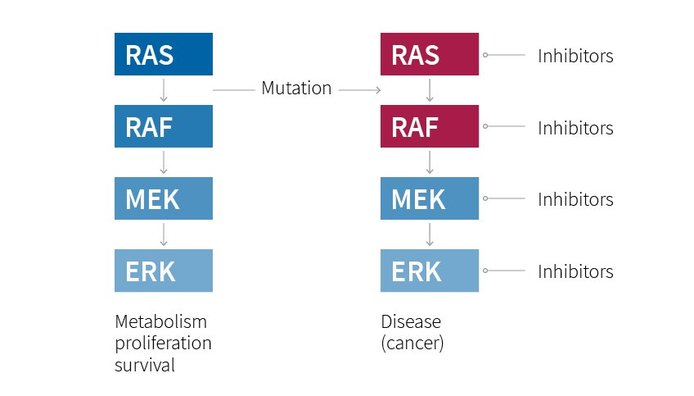

Signals travel through a cascade of proteins to maintain cell metabolism, proliferation and survival. Mutations in this cascade (red ellipses) can lead to diseases including cancer. RAS is the most potent human oncogene. Chemical inhibitors of cascade components are already in the clinic for cancer treatment, and more are being developed.

Rudolphina: What can happen if something goes wrong in signalling?

Baccarini: The activation of the pathway is a key event in several diseases. This cascade is most known for its role in cancer and has therefore been for decades one of the ’hot topics’ studied by cell and cancer biologists, but also by pharmacologists and clinicians. The cascade is activated by the most potent human oncogene, RAS, and the entry point in the cascade, RAF, is also found mutated in specific cancer types. Thus, the proteins in this pathway are attractive therapeutic targets, and several small-molecule inhibitors are in clinical use.

Rudolphina: How are you shedding light on the ’signaling highway’?

Baccarini: We are trying to find out how the three proteins RAF, MEK and ERK work, what they do in the cell. To do this, we started to take out the genes coding for these proteins and observe the changes this caused model organisms in vivo. But our cells have an ’emergency plan’: If you delete any protein, there is almost always another one that can take over its function. So, more recently we have decided to look at things in a different way and investigate the social network of the proteins. We fused ’our’ proteins with an enzyme that permanently modifies every protein that comes into contact with ’our’ proteins. By labelling the environment, we can generate a map of interactions and have already had some exciting surprises.

Rudolphina: What is your favorite discovery so far?

Baccarini: My favorite discovery came from the analysis of RAS-driven tumor models. It was the first evidence that the protein RAF1 must be present for RAS-driven cancer to develop and be maintained.

Rudolphina: Can your research lead to new cancer therapies or drugs?

Baccarini: What keeps me and my team going is the idea that our work might create something beneficial for society. I like to think of our work as basic research that opens the doors for further possibilities, and that the data we generate can be used by scientists with different backgrounds. The Max Perutz Labs are a great location for that: Various disciplines come together and we have all the facilities that allow us to do interdisciplinary work. Realistically, however, the road leading from changes observed in the lab to new therapies or drug is a very long one. For the specific case mentioned above, it is gratifying to see that pharmacological research is currently investing in the development of experimental drugs that are able to cause the degradation of specific RAF proteins.

Rudolphina: You have been working with cells since the beginning of your scientific career. How did the field change?

Baccarini: The big revolutions in science happen when new techniques make new things possible. There have been a couple in my career, but the game changer in all fields is the availability of high throughput methods. We can interrogate cells in a breadth and depth that was not possible before. With big data we get a more complete picture – that is not always easy to interpret.

Vienna Doctoral Schools

About 5,000 doctoral candidates from 110 countries study at the University of Vienna. The Vienna Doctoral Schools of the University of Vienna prepare these early stage researchers for their future careers in the best possible way, placing great emphasis on state-of-the-art methods and techniques, intensive supervision by top researchers and networking within the academic community. Workshops, seminars, research excursions, retreats and summer schools contribute to a lively and international peer culture.

Rudolphina: Early stage researchers today need different skills to succeed in science than maybe twenty years ago. What is your advice for young researchers?

Baccarini: Two things that I also try to communicate and implement in the Vienna BioCenter PhD Program and in the FWF-funded PhD track Signaling Mechanisms in Cellular Homeostasis: First, do not stay in your own box but be open to new ideas. Interdisciplinarity is key! Second, keep up with new technologies and understand the way data is analysed – this can only be done in the context of a true collaboration between the scientists who generated the data and the scientists that analyse them. Sophisticated technologies and data analysis programs are great, but they work only in combination with scientists who are able to do a ’sanity check’ and interpret the results of the analysis with the biology in mind.

Rudolphina: Thank you for the interview. (hm)