Can art keep you healthy?

Most of us love going to museums and admiring the works of Monet, Picasso or Klimt. However, art can not only inspire us, but may have a much profounder impact than we thought. Art can increase our resilience, it has a positive influence on our blood pressure and it might even strengthen our cognitive abilities. To engage in art seems to be particularly healthy for our mind and body. What's more, it could have an influence on very serious illnesses. For example, researchers have frequently reported that people suffering from Parkinson's show changes in their inclination, interest and even ability to create art.

Therefore, it is particularly intriguing to look at the role of art and creativity in the life of people who suffer from neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's. In the project Unlocking the Muse , researchers want to find out more about this seemingly deep connection, what it tells us about the disease itself and how this knowledge can be used to help people who suffer from Parkinson's. This project unites an international and interdisciplinary consortium of art researchers and neuroscientists, led by Matthew Pelowski from the Faculty of Psychology and Julia Crone and Blanca Spee from the Vienna Cognitive Science Hub of the University of Vienna. In the project, they are collaborating with the Radboud Medical Centre in the Netherlands and the Donders Institute , Center of Excellence for Parkinson's Disease.

The muse is awakened – but how?

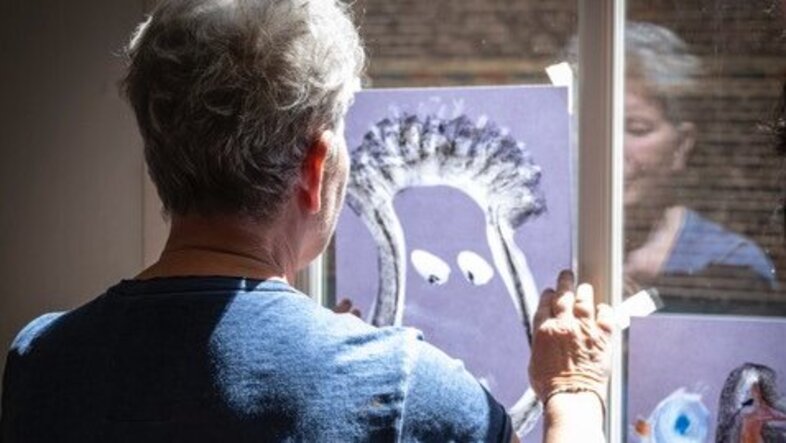

"There is quite a lot of anecdotal, emerging evidence that people suffering from Parkinson's disease might be changing their attitude towards art. Out of the blue, they can develop a sudden interest in making art and feel very creative," says Pelowski, who coordinates the research project. "Our question is, whether we actually find these changes in a large-scale, systematic and collaborative series of studies, and why the relationship between art and creativity is changing in Parkinson's patients." To get to the bottom of this, the team began studying the changes in creativity of around 800 people with Parkinson's, to examine how their lives and possibly their brains can be creatively stimulated.

For this, the interdisciplinary team uses a wide variety of methods, "We always start with a pilot study and a multi-method approach. This includes patient participation and interaction research, as well as interviews and many evaluation rounds. It is quite complex, managing all these different perspectives, but I believe that this is what makes our research so foundational," explains Spee, who works at both the University of Vienna and the Radboud University.

From survey to neuroimaging

During the interviews, the researchers ask basic questions like, 'Did you notice a change in your creativity' or, 'Have you observed that you make more creative products?'. They follow up with questions concerning the participants' creativity at different stages in their lives: before they were diagnosed, after they were diagnosed and after starting to take medication. So far, they have found that over 40 % of people with Parkinson's experience a change in their creativity. "About 15 % of the participants say that their creative interest increases and about 20 % say they have lost their creativity," says Pelowski.

The next step is to observe the brains of the study participants using neuroimaging and brain stimulation with a device that uses ultrasonic waves to target specific brain regions. "We try to directly target the networks in the brain which we think are involved," explains Julia Crone. "We know, for instance, that the dopaminergic system seems to play a key role in the whole mechanism. Hence, we started our pilot study with the striatum, an area deep in the brain, which is very heavily involved in the dopaminergic system and also in the reward system and which is also the target for commonly used drugs given to Parkinson's patients," explains the neuroscientist.

For neuroimaging, the researchers use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). "We will use the stimulation on healthy volunteers to see if we can reproduce some of the changes in creativity as suggested," says Crone. In a first step, the participants are observed, while they are undergoing targeted stimulation and secondly, the volunteers perform some creative tasks to see how the brain responds to these tasks after stimulation as compared to no stimulation.

"That is the exciting thing about this project. No one has tried to specifically target specific areas in the brain or do something to the brain causally to modulate creativity. This is a very new thing. On the other hand, we are quite aware that one cannot transform someone into a Picasso with the push of a button," laughs Crone.

Flexibility wins

Another important aspect that is related to creativity and Parkinson's is the so-called cognitive flexibility, which reflects how easily you respond to your environment.

"Humans are always confronted with an overflow of stimuli, so we need this cognitive flexibility to adequately respond to the changing environment while still being able to concentrate on one thing," says Crone.

It has been shown in previous studies that patients with neurodegenerative diseases are impaired in cognitive flexibility and also in brain variability. Both are known to decline with age and performance. This in turn means that people with higher cognitive flexibility and brain variability perform better at certain tasks and are less likely to develop neurodegenerative diseases.

"So higher cognitive flexibility might protect you from neurodegenerative diseases," suggests the researcher. Again, the striatum plays a big role here, "To be able to focus and process all the information coming in, you need a balance between focus and flexibility. The striatum helps to keep this balance," says Crone.

Even the jobs people had over their lifetime seem to have an effect and may help to protect the brain: Researchers found that people who developed Parkinson's disease were eight times less likely to have had a creative or arts-related job.

"Training cognitive flexibility is good for almost every aspect of your life and has a protective factor. When people retire it is important to keep doing activities, such as learning other languages and doing some sort of creative tasks," Pelowski explains.

Challenges and changes

As part of their project, the team around Pelowski, Crone and Spee must dive into a completely new area, which does not come without challenges. "Everything is very exciting, new, wonderful and I love it – but this topic is also based on very little knowledge," Crone says. There are still many questions to ask and many more experiments to run, which are essential to the next stage, "The hardest aspect is to find the most effective method and the perfect questions to ask to obtain the right answers," explains Crone.

Many of the project's challenges also lie in the peculiarity of the disease and its very diverse symptoms. "Parkinson's is not just one disease; it is many," says Spee. "You look at ten people with Parkinson's and you are not just faced with ten different personalities, but you are faced with ten different versions of the disease". To be open to this diversity, the researchers need to create study designs that are complex enough, yet still generalisable. "What blows my mind is how much we learn from the people with Parkinson's themselves! Not only do they improve the quality of our research but they also support us endlessly in developing all sorts of research programmes and interventions. It is amazing how much they contribute, particularly in helping others, who might be in their early stages or at risk of developing the disease," emphasises the neuroscientist.

A multi-faceted disease such as Parkinson's requires a multidisciplinary mindset and the cooperation of several disciplines, such as social sciences and neuroscience, over extended periods. "We are very grateful for this long-term transdisciplinary funding and are very curious to see what we will discover next," says Pelowski.

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease is one of the most common diseases of the central nervous system. It manifests itself in motor and non-motor symptoms and there is no cure for it up until today. Due to global lifestyle changes, it is the most rapidly increasing neurodegenerative disease worldwide affecting men and women equally.

As the neurodegenerative disease progresses, more and more neurons that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine die. Since dopamine is responsible, among other things, for controlling movements, the movement disorders typical of Parkinson's disease increase in severity. These mainly include slowed movements, stiff muscles and muscle tremors, but also affect cognition and emotional experience.

The disease usually occurs in the second half of life. In Austria, around 20,000 people are affected.

Parkinson's disease affects...

...about 1 in 250 people over the age of 40

...about 1 in 100 people aged 65 and older

...about 1 in 10 people aged 80 and older

Currently, he is coordinator of the FWF #ConnectingMinds Project Unlocking the Muse, as well as coordinator of an EU Horizon 2020 project under the funding scheme TRANSFORMATIONS-SC6-2019: Societal challenges and the arts.

With a master's degree in Business Economics and a doctoral degree in Psychology specialised in neuroaesthetics, her expertise extends to neuropsychopharmacology and developing intervention programmes in healthcare systems. Currently, she is Co-Principal Investigator of the project Unlocking the Muse (CM1100-B, Austrian Science Fund (FWF)), focusing on art-based, person-centred intervention, epidemiology and the study of brain changes impacting creativity and cognitive flexibility in people with Parkinson's.

She and her lab is interested in complex interactons, network dynamics, as well as intense conscious experiences.