Regulating AI: Are we on the right track?

Why does a sausage stand in Vienna have to fulfil more requirements than a socio-technological experiment worth billions? Currently, companies may put AI language models on the world market without any external quality assessment, even if the product has millions of users within only a few weeks. If you consider this problematic, you are quickly labelled anxious, technophobic or even anti-enlightenment.

Many believe that the law is not fast enough in reacting to new technologies, that the Internet cannot be territorialised or that social media cannot be controlled. In addition, we observe a fascinating reluctance to apply existing legislation. There is, in fact, no shortage of regulation, for example in the form of data protection law, copyright or competition law. The phenomenon of AI is certainly not a new one. Some of the methods used have existed for decades.

Regulation as Europe’s last innovation?

In parallel with the hype surrounding the alleged technological innovation, Europe has been working on another innovation – a suitable legal framework. This is also challenging. Who is still able to follow all the latest changes and understand them in a broader context? The European Commission under Ursula von der Leyen alone has introduced around 40 acts, including the Digital Markets Act as well as the Digital Services Act and recently the much-debated AI Act: a complex collection containing more than 450 pages, hard-to-understand regulations, partially unwieldy or imprecise language and plenty of political compromise.

The AI Act falls under classical product safety law. The concept is simple. It is based on an assessment of risks posed by the technologies: It prohibits high-risk systems, softens high risks by introducing strict quality and security requirements and does not regulate low-risk systems. Imagine an AI system that tries to predict, based only on a person’s citizenship or place of residence, whether or not this person will commit a crime. This would be prohibited under the AI Act since this AI system does not comply with European values, in particular the presumption of innocence. Using an AI-based robotic care assistant in a retirement home is permissible though. However, to protect the privacy and human dignity of the person affected, such systems must fulfil strict quality and security requirements. And when you use Fred, the chatbot of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Finance, the system must clearly show that you are communicating with an AI.

In addition, also AI models that have a general purpose, such as AI language models, will soon have to comply with strict regulations; at least, if they are expected to entail systemic risks. Providers of these models must, among others, present a strategy for compliance with copyright and fulfil cybersecurity requirements to an appropriate degree. The regulations on how to categorise models into those that entail systemic risks and those that do not certainly seem like a closed book.

Societal impact of the AI Act

But what does this Act mean for us citizens? Not much, for the time being – the Act primarily has implications for the industry. It thus ensures health and product safety, as is common also in other areas. But the Act is also innovative. It puts the protection of fundamental rights, the environment, democracy and constitutional state before product standards.

However, contrary to what these terms might suggest, these regulations do not empower individuals. Violations of fundamental rights are not enforceable, citizen participation is not intended and it is almost impossible to take legal action against a violation of this law. Even the rights of the persons affected and rights of appeal that were introduced last minute are doing nothing to change this. These rights allow individuals to report violations of the law and they grant persons affected by AI decisions a right to transparency and to receive an explanation. However, this is only marginally related to the traditional protection of fundamental rights, since the law delegates the protection of these values primarily to the industry and administrative bodies that make use of AI.

Who is allowed to experiment?

The criticism of the AI Act is justified, both from the perspective of content and legislation. The Act is overwhelming and regulates too much and too little at the same time. It presents the industry with tasks that are expensive and difficult to resolve. At the same time, it does not provide protection, or enough protection against many dangers, such as AI-based war technology or the extensive impact on the climate.

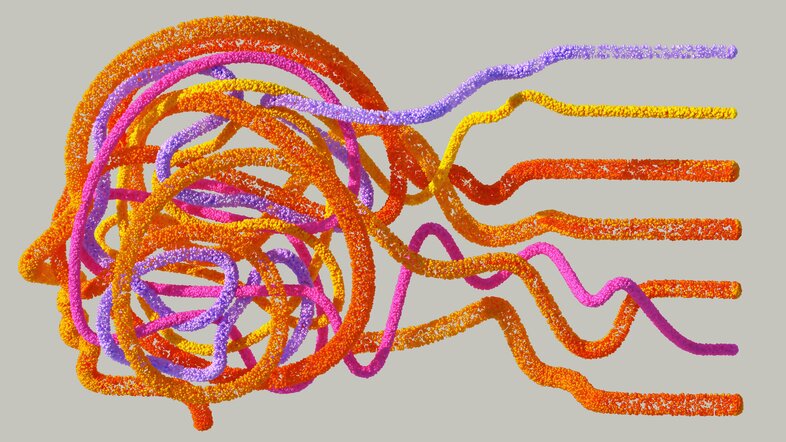

But the Act is much better than the poor reputation it now already has. Do we want to exist in a world of AI-based classification which is mediatised by technology and in which humans are gradually turning from subjects with fundamental rights into objects controlled by technology? Or do we still want to live in liberal, constitutional democracies five years from now? A world in which we still have freedoms in future that allow us to grow and develop and be different. Those who hope for this kind of future have to accept that democracy and the constitutional state are expensive and require both time and academic expertise.

- The German-language version of this article also appeared on derStandard.at as part of the cooperation on the semester question.