Who wrote Byzantine history?

From the pinnacle of power to a sudden decline and the rise of the Crusades: In her research project RELEVEN, Tara Andrews aims to cast a clearer light on the events of the "short eleventh century" in the eastern Christian world – the Byzantine empire and its neighbours – between 1030 and 1095. "It is a really fascinating time period when everything seems to have gone from perfectly wonderful to absolutely terrible", explains Tara Andrews, a historian who has been awarded a prestigious grant from the European Research Council for her work on Byzantine, "We have a lot of information about the big events, but meanwhile people were living ordinary lives and writing history as well. My research team and I are trying to get a better understanding of the ways in which the Christian world was perceived by the inhabitants at that time."

Byzantine Empire per definition

Byzantium was an empire in the eastern Mediterranean founded in 330, the successor to the Roman Empire. It ended with the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453. Byzantium has produced significant works of law, literature, and art and it played an important role in the Christianisation of Europe. At the beginning of the eleventh century the empire was ruled by Basil II "the Bulgar-slayer" and soon reached its largest extent since the sixth century; by the end of the century, much of its eastern territory was lost to civil war, Turkish invaders, and Crusader warlords.

Overlooked sources in text and material

In order to put the puzzle pieces together, Tara Andrews is investigating and in some cases digitising material resources from all over the region: Text sources, such as history books, overlooked hand-written notes in manuscripts, collections of letters and land property registers that serve as narrative records, as well as material sources, such as coins, seals and inscriptions from churches in the Caucasus. To do so, Andrews and her team have travelled to their origin, "We recently went to Yerevan to get a batch of manuscripts and we may yet have to go to Jerusalem to get some more". However, they mostly track down illuminating documents in online collections. "Some are already published online, but many of them we do have to order from archives either as manuscript images or take our own photos", explains Andrews, Professor for Digital Humanities at the University of Vienna.

Recording different perspectives

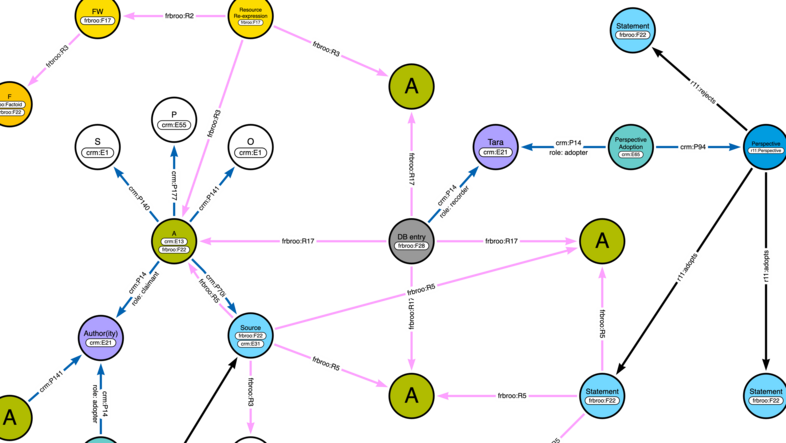

The development of a digital open source database is an integral part of RELEVEN, but the overall goal of the project goes further: Instead of simply digitising facts, Andrews and her team want to record different opinions and interpretations of historical facts. For instance, the researchers work on the Armenian colophons – the notes that are left in manuscripts by the copyists. "Armenian texts have quite a rich colophon tradition. They contain a lot of information about what was going on at that time. Some of them are entire mini chronicles on their own", says the team leader. "The main historical sources for this period would have us believe that Armenian society was teetering at the edge of ruin. But colophons are not giving this impression. It's a wonderful first example of how we can reveal different perspectives on historical facts in our project."

Making power structures visible

To demonstrate these multiple perspectives, Andrews and her team developed a new model of structuring and presenting the data. Andrews explains their model’s general rule of thumb: We add the authority information, i.e. who claimed a certain fact to be true and the source information, which says on what basis did they say it was true. Thereby, Andrews and her team are trying "to make the power structures transparent rather than glossing over them".

Beyond static categories

Presenting complex social history in a data model needs reflective and critical thinking. For example, in order to investigate the characteristics of actors in history, Tara Andrews and her team draw on the data of the Prosopography of the Byzantine World by researchers of the King's College London. "This database employs three gender categories: male, female and eunuch. What we found kind of problematic was the fact that gender is always a static category, whereas we know that a eunuch is usually someone who was born male and was castrated at some point during their life." Instead of thinking about gender as a category, in their database Andrews and her team treat gender assignment as an event, which allows them to add more context.

Making historical data accessible

Most people search for digital historical information on Wikipedia, "which is great but only to a certain extent. With our database, we try to show the authority and where the information comes from”, says Tara Andrews, who is trying to make the multi-faceted history of Byzantium accessible. "In the long term, our database can be used – by scholars and non-scholars alike – to collect several viewpoints from the universe of assertions." (hm)

How does digitalisation affect democracy?

During our current semester question, our experts address the question of how much algorithms democracy can take – and how the digital transformation can help to strengthen democracy again – from different perspectives. Read more (in German)!