How illiberal are Europe's right-wing parties?

How illiberal will the European parliament (EP) be after voters cast their ballot in the June 2024 elections? Opinion polls predict a significant increase in representation of parties often called "populist", "illiberal", or simply "the extreme right". It stands to reason that if these parties become stronger, the EU may substantially revise its policy emphasis from being a promoter of culturally left policies (like environmental and gender equality) to more restricted and conservative policies (like border security and anti-immigration acts ).

An illiberal EU parliament?

Underlying such an assessment, however, lurks an important question: if the cultural extreme right increases their presence in the EP, how illiberal will the new parliament be? A party is illiberal, according to Jane Mansbridge, when it seeks to challenge the "constellation of constitutional principles and practices that protect the individual from the state." This understanding focuses on the rule of law, procedural protections for political minorities, and the division of power among the judiciary, executive, and parliament.

Thus, an important question is, to what extent do right-leaning parties in the European parliament favour weakening constitutionally guaranteed principles, such as curbing the authority of the judiciary and restricting the free media? While parties may not openly advocate their illiberal goals, many pundits and experts seem to think that a rightward cultural policy shift by the EP will prompt a growth in illiberalism.

This is because the two aspects seem intertwined: most illiberal parties also favour culturally conservative or even extreme right policies (like anti-immigrant and anti-LGBTQ+ policies). Illustrative examples include Hungary, Poland, and — beyond Europe — Israel and the US.

Postgraduate Master's Programme in European Studies

This postgraduate master’s program equips students with academic, practice-oriented and interdisciplinary knowledge of the economic, legal, political and socio-cultural development perspectives of European integration. Furthermore, it aims at analyzing specifics of information and knowledge management within the European Union.

Click here to learn more about the programme. Applications for the winter term 2024 are open; residual spots will be available past the 31st May deadline.

Right-wing parties come in different flavours

However, case studies conflict with such sweeping assessment. They suggest that there exists quite a bit of variation in the degree of illiberalism even among the culturally extreme right. While some parties in this genre (like Hungary’s Fidesz, the Polish PiS, or the German AfD) are clearly illiberal (they wish to weaken constitutional courts, lower the protection of political minorities, and curtail a free press) — others like the Dutch PVV or the Norwegian Fremskrittspartiet appear to eschew a clear-cut focus on illiberal policies.

Contributing to this ambiguity, research about the degree of illiberalism among parties remains in its infancy. There are few systematic attempts to empirically measure and describe the extent to which parties — including culturally conservative ones — fit the illiberal profile. Thus, one central question of a research project I have been involved in for nearly a decade is: what evidence exists to systematically describe the degree of illiberalism among all parties in Europe, but particularly among parties that are on the cultural extreme right?

How illiberal are the culturally extreme right?

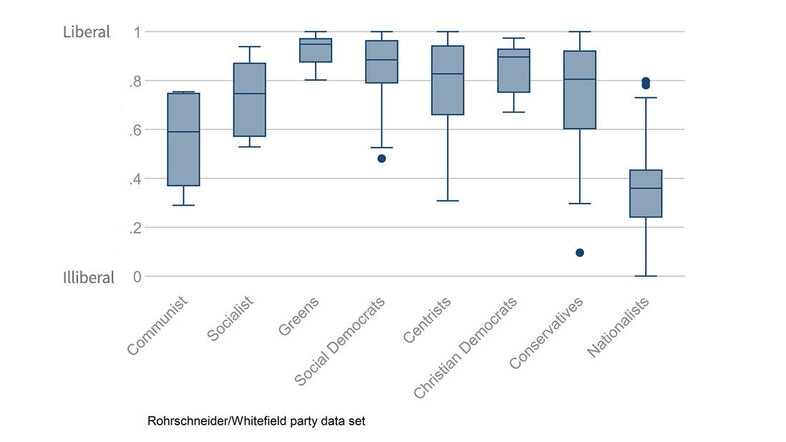

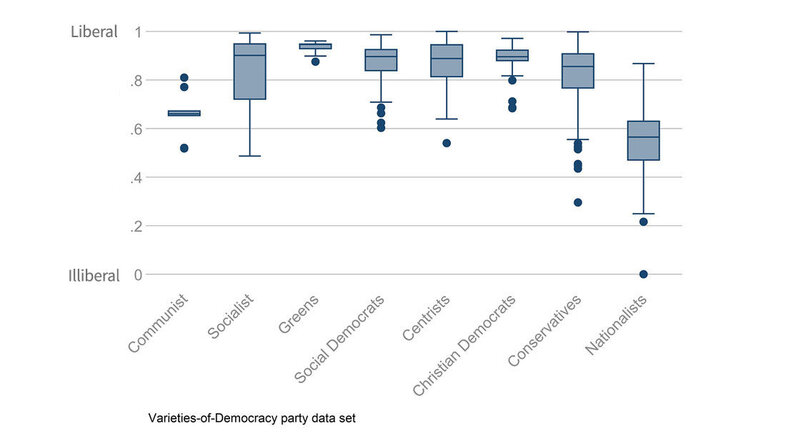

Let us begin by looking at the degree to which parties pursue illiberal policies. In collaboration with Stephen Whitefield (University of Oxford), we collected data on 24 European democracies to assess whether parties sought to undermine the constitutional protections designed to "protect individuals from the state." When we asked country experts to rate 205 parties on their illiberal and authoritarian policies, we corroborated the results by an independently acquired party-level data set from the University of Gothenburg released by the Varieties of Democracy project.

After grouping the parties into "party families", a conventional way of summarizing the shared programs of like-minded parties, e.g., communist, greens, centrists, nationalists, our analysis captures the level and variation of illiberalism within these families.

We first note an expected pattern. The bulk of mainstream parties — Greens, Social Democrats, Centrists, Christian Democrats — are located on the liberal end, approximating full liberalism. Also, most parties within these families generally fall into the liberal camp. The socialists on the left and Conservatives on the right are still firmly located on the liberal side.

In contrast, the two extremes — Communists and especially Nationalists (which capture extreme right parties) — are much lower, on the illiberal side. This is the expected pattern — the median and ranges for ideologically extreme parties are much more likely to represent illiberal policies than more mainstream party families.

Nationalist parties are scattered across the liberal-illiberal spectrum

However, we notice considerable variation within each party family. While mainstream party families largely stay within the liberal range (though even here we notice an occasional lurch into illiberal territory, especially for Conservative parties) — the nationalist party family covers the full spectrum, from fully illiberal to squarely liberal. This means that we cannot automatically assume that all culturally right-extreme parties are illiberal because several of these parties seem ready to endorse constitutional principles.

Conclusion: Illiberalism and the 2024 EP elections

On balance, we must know two things to assess the implications of the likely rightward shift of the next EP. First, and obviously, what is the relative strength of party groups? For example, how strong will the Identity and Democracy (ID) and European Conservatives and Reformists ECR) become? These party groups typically meld parties from the nationalist right into a European party group so we need to know their representation.

However, we also need to know more about the exact composition of these party groups. Are these composed mainly of clearly illiberal parties? Or do most of the culturally extreme right parties in the ID and ECR groups endorse liberal democratic principles?

The answer to this question will shape the character of these groups and thus influence the nature of the next European parliament. For example, if the ID group is dominated by less illiberal parties (like the Le Pen-led French National Rally (RN) of late), the ID will develop a different tone in the next EP than if the ID group is dominated by parties like Fidesz (to name one example). Likewise, the presence of more or less illiberal parties in the ID and ECR will affect its internal cohesion. For instance, the ID recently announced that it now excludes the illiberal AfD from the ID parliamentary group in the current EU parliament.

All told, a central reason to study the range of illiberalism among parties is to understand the implications of a greater presence of right-wing parties in European parliaments and governments — a topic too important to ignore.

His research interests include political parties and public opinion in European countries. He is currently a Fulbright - University of Vienna Visiting Professor of Social Sciences at the Department of Political Science at the University of Vienna.

- Democracy Facing Global Challenges: Varieties of Democracy Report 2019

- Jane Mansbridge: The Evolution of Political Representation in Liberal Democracies: Concepts and Practices

- Robert Rohrschneider - Fulbright – University of Vienna Visiting Professor of Social Sciences at the Faculty of Social Sciences

- Department of Government at the University of Vienna